How much water should you drink a day? – Elixir of life for mind & body

- What role does water play in our body?

- Thirst and Drinking Behaviour – How much water do we need?

- Water and Nutrition – Choosing the Right Drink

- Dehydration – The Water Balance and the Body’s Response

- How much water do I need?

- Conclusion: 10 things you should know about water

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Sources

Not only did the first life on earth evolve in water, but we humans also consist largely of this essential compound and use it for a wide variety of purposes. Personal hygiene, cooking, cleaning and leisure activities such as swimming would be almost impossible without water.

Aside from these uses, water has another, more existential significance for humans. Without sufficient hydration, the human body shuts down even faster than it does without food. But why is that?

- Why do we need to drink water regularly?

- What do we need it for?

- How much water (chemical formula H₂O) should we be drinking every day?

We will answer all these questions in the course of this article. Prepare never to take this life-giving liquid for granted again.

What role does water play in our body?

The following simple rule applies:

The more muscle mass and the less body fat you have, the greater the proportion of water in your total body mass.

The reason is that muscles can store water, while adipose tissue holds very little water. Due to human physiology, men contain a slightly higher percentage of water than women.

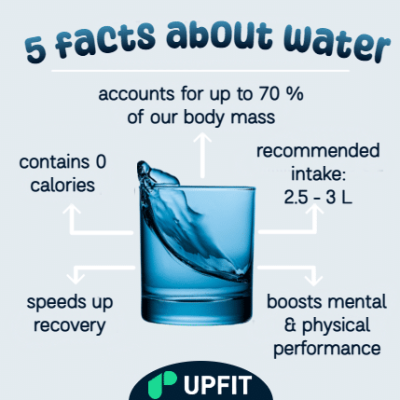

Water makes up between 50 and 75 % of human body mass.

However, various circumstances can also lead to unfavourable water retention. Here you can find out how water retention occurs and how you can quickly lower your hydration levels. Here you can find out how water retention occurs and how you can quickly lower your hydration levels.

The Water Balance

The water in our body is distributed between two different areas:

| WATER OUTSIDE CELLS | WATER INSIDE CELLS |

|---|---|

| Interstitial space, plasma and transcellular space | Intracellular space, mainly cytosol |

| Composition: potassium, phosphate compounds und proteins | Composition: mainly sodium chloride (table salt) |

These areas are involved in a constant exchange that keeps them in balance.

This balance refers not only to the amount of water in the two areas, but also to the composition of this water, which contains potassium, phosphate compounds and proteins inside the cells and mainly sodium chloride (table salt) outside.

You may have heard the phrase “electrolyte balance” before, the technical term for this balance. Without the state of equilibrium between the two areas, our body would not function properly: numerous vital cell functions would not be possible and our metabolism would come to a standstill.

Thirst

The mechanism that regulates our body’s hydration is thirst.

Thirst makes us drink water to make up for lost fluids. What you probably didn’t know is that there are two types of thirst that arise for different reasons, and there are also different mechanisms that stop you from feeling thirsty.

Thirst and Drinking Behaviour – How much water do we need?

Our body is constantly losing water via evaporation (insensible perspiration, respiration), sweat and excretions, which we need to replace.

Physical activity and the resulting sweat increase this requirement, as do heat and other external factors.

How much water should you be drinking per day, then?

Depending on our size, weight, muscle mass and gender, we need to consume between 1.5 and 3 litres of water per day.

How does thirst arise?

But when does our body react, and in what way exactly? This is where it gets a bit scientific! If you are not interested in the physiological background, just skip the next two sections.

Our body reacts very sensitively to a loss of water. Even with a water loss of around 2 % or around 0.5 % of body weight (e.g. via sweating), the electrolyte balance in the extracellular space (the space outside the cells) changes to such an extent that steps must be taken to reestablish the equilibrium.

| Osmotic Thirst | Hypovolaemic Thirst |

|---|---|

| Our body cells release water into the extracellular space, thereby shrinking, and the signal “thirst” is generated. The volume of liquid decreases and the composition of the water changes. | The volume of liquid decreases, but the composition of the water remains unchanged e.g. via blood loss). |

| So called because the process is triggered by a change in the composition of the extracellular water (osmolality). | So called because the process is triggered by a lack of volume (hypovolaemia). |

The liquid outside the body cells (the extracellular water) is a kind of saline solution, which is why we crave salt regularly, but not in synchronisation with our thirst.

Both triggers work synergistically and trigger the same feeling of thirst, but osmotic thirst is much more common and therefore dominant.

Tip: Now would be a good time to have a sip of water!

Drinking and Quenching Thirst

At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter how thirst arises – if you’re thirsty, you should drink something.

We all probably believe that quenching our thirst is a natural process that has been bestowed upon us by evolution. However, this is only partly true, because our drinking behaviour is largely learned.

Sensors in the pharynx, stomach and duodenum “record” our need for water based on experience. Time to grab a glass of water! When you drink something, you relieve your thirst instantly.

Your thirst is quenched long before your body’s lack of water is actually compensated, as absorption of water via the digestive system takes some time. The body thus has to estimate the amount of liquid it requires and, in fact, does this very precisely. Thethe process is called pre-absorptive quenching.

The body aims to keep fluctuations in the water and electrolyte balances as low as possible, since they have a massive impact on our performance (see “Dehydration” below). For this reason, our body learns to drink more when eating salty foods, for example, in order to be able to process the high salt content and keep the electrolyte balance stable.

In the end, we rarely drink to fix our water balance (i.e. primary drinking, thirst), but rather preventatively, through learned drinking behaviour (i.e. secondary drinking), as in the example just mentioned. Ideally, we’d never feel thirsty because we’d keep drinking small amounts of water regularly to prevent the body from reaching the thirst threshold, which is about 0.5 % loss of body weight in water.

Water and Nutrition

Larger fluctuations in the water balance are common in most people, for example…

- because they haven’t learned beneficial drinking behaviours,

- because water is not always immediately available when thirst sets in,

- due to exercise or other forms of physical exertion,

- because external factors such as heat and humidity also influence the water balance during physical activity,

- because they suppress their thirst,

- because they choose the wrong drink.

In particular, your choice of drink is heavily dependent on learned drinking behaviour and is to blame for several issues. When we’re thirsty, our bodies need water and electrolytes, but not necessarily energy.

| SUITABLE DRINKS | UNSUITABLE DRINKS* |

|---|---|

| Still mineral water | Soft drinks |

| Tap water | Juice drinks and Juice |

| Unsweetened tea | Alcoholic drinks |

| Infused water | Alcohol-free beer |

| Squash (with 4 parts water to one part squash – occasionally, during exercise) | Smoothies |

| Isotonic drinks | Coffee-based drinks (e.g. mocha, latte) |

| Black coffee (occasionally) | Dairy drinks (milk, milkshakes) |

| Diet drinks (rarely) |

* Unsuitable does not necessarily mean unhealthy. Smoothies, for example, are very nutritious but contain lots of calories and are therefore not a suitable choice for quenching thirst.

All drinks that contain calories provide us with energy that we only need in exceptional cases (e.g. when running a marathon). As you probably know, excess calories are stored as fat deposits in our bodies.

But it’s not just the calories that are a problem. Even diet drinks without calories cannot replace water. They contain flavourings and often carbonic acid or caffeine too, which have an impact on our water balance and make them poor thirst-quenchers.

Alcoholic beverages are even worse at quenching thirst. They completely disrupt our water balance, as they bring liquid into the body, but at the same time greatly increase water loss due to the fact that the body has to break down and excrete a toxic substance – alcohol. The pounding headache you get the day after binge-drinking is nothing more than a symptom of severe dehydration caused by alcohol’s interference with your water balance.

So are diet and zero-sugar drinks not a good alternative to sugary soft drinks? Find out here.

Dehydration – The Water Balance and the Body's Response

The buzzword “dehydration” has cropped up several times in this article already, but what exactly does it mean?

Dehydration roughly means the loss of a significant amount of water from the body.

Isotonic dehydration is when the body loses both water and salt, for example as a result of:

- diarrhoea

- vomiting

- heavy sweating

- alcohol consumption

Hypotonic dehydration, where more salt is lost than water, can occur following burns, while hypertonic dehydration, the opposite, can be a symptom of diabetes.

Unbalanced dehydration leads to exsiccosis, with symptoms ranging from mild to dangerous, depending on the severity of a case. In severe cases, hypovolaemic shock may occur, which can be life-threatening.

How much water do I need?

The best measure of whether or not you’re drinking enough water is the colour of your urine.

The more substances are excreted by the body, the higher the osmolality and the darker your urine. Since we all have to do our business on a regular basis, it’s a great way to check our fluid intake regularly.

Dark urine means you’re not drinking enough water.

Calculate your daily water requirement

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota developed the following formula to calculate how much water a person needs in a day, not counting additional water required due to heat or exercise. You can use it to calculate your base daily water requirement (i.e. how much water you should be drinking each day without factors such as exercise and temperature).

Weight (in kg) x age (in years)

————————————————- = ounces* of water / day

28.3

*1 ounce = 0.03 litres

It is important to note that the body finds it easier to maintain its water and electrolyte balance if smaller amounts of water are consumed at regular intervals.

If you spend 16 hours of the day awake, you can follow this simple rule: “Drink a glass of water (0.15 – 0.2 L) every hour”. This way, you’ll get about 2.4 – 3 litres a day and thus achieve an adequate fluid intake.

Tip: Cups of black coffee and tea count towards your glasses of water too.

The benefits of drinking an additional litre of water every day

Have you had problems drinking enough or drinking regularly, or have you simply got into the habit of drinking things that don’t keep your water balance stable? If yes, you should consider the numerous advantages of an adequate water intake:

- More energy

- Better ability to concentrate

- Better physical performance

- Better immune defence

- Less chance of gastrointestinal problems

- Less weight fluctuation

- Faster recovery periods

Water, Exercise and Other Factors

Above all, warm temperatures and exercise can significantly increase your water requirement due to the heavier sweating they cause. In hot weather, you should be drinking at least an extra litre.

On days when you do a lot of exercise, your water requirement doubles or even triples.

Conclusion: 10 things you should know about water

Last but not least, we want to give you a few quick facts to encourage you to improve your drinking habits in the future:

- Your body consists mostly of water

- The body can’t function without water

- If you’re thirsty, you should drink water

- Still mineral water is the best choice of drink

- Your drinking behaviour is learned and can be changed

- If you drink enough water throughout during the day, you will be more productive

- Little and often is better than drinking large amounts of water sporadically

- Exercise and heat increase your water requirement

- Alcohol consumption, diarrhoea and vomiting lead to dehydration

- Dehydration causes unpleasant symptoms and should be remedied as quickly as possible

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I drink water even if I’m not thirsty?

Yes! It is recommended that you drink continuously throughout the day. This keeps fluctuations in the water and electrolyte balance as low as possible. The feeling of thirst should be regarded more as a kind of “alarm signal” from the body.

What happens if I drink alcohol to quench my thirst?

Alcoholic beverages are indeed liquids, but the toxins they contain must be processed and excreted by the body. As a result, alcohol consumption actually leads to a loss of water, which becomes apparent – usually the next day – in the form of a headache.

Do I always have to drink 2 litres a day?

It is not possible to specify exactly how much water you should drink, as your required fluid intake depends on many factors. Depending on personal characteristics such as gender, age and body size, as well as ambient temperature and intensity of physical activity, the recommended intake of water varies greatly. Exercise, for example, can double or even triple the amount!

Sources

- Schmidt; Lang; Thews (2004). Physiologie des Menschen (29th edition). Springer, Berlin.

- Behrends, J.(2009) Physiologie. Thieme, Stuttgart.

- Gekle, M.; Wischmeyer, E.; Gründer, S.; Petersen, M.; Schwab, A.; Markwardt, F.; Klöcker, N.; Baumann, R.; Marti, H. (2010). Taschenlehrbuch Physiologie. Thieme, Stuttgart.

- Augustine, V. (2019). ‘Neural Architecture Underlying Thirst Regulation’. Dissertation (Ph.D.), California Institute of Technology.

- Silbernagl, S.; Despopoulus, A. (2007). Taschenatlas Physiologie (7th edition). Thieme, Stuttgart.

- Libuda, L.; Muckelbauer, R.; Kersting, M. (2009). ‘Getränkeverzehr und Übergewicht bei Kindern’ in Journal für Ernährungsmedizin 11(23).

- Evers, K. (2009). Wasser als Lebensmittel. Behr’s, Hamburg.

- Murray, B. (2007). ‘Hydration and physical performance’ in Journal of the American College of Nutrition 26(5).

- Elmadfa, I. (2009). Ernährungslehre (2nd edition). UTB, Stuttgart.